by Jean Roberta

I’ve written here before about my comfortable niche in the English Department of the local university, where I teach nuts-and-bolts composition and literature to first-year students plus the occasional course in creative writing. I have access to funding for writing-related travel, which includes erotic writing conferences, readings, and award ceremonies. Every three years, I submit a Faculty Review Form on which I brag about my accomplishments, including publications. Before I compiled my list for 2011-2013 inclusive, the friendly department head told me that I don’t brag enough; he advised me to list every review and blog post I’ve written, as well as every erotic story I’ve had published and every panel I’ve sat on. His summary of my latest Faculty Review begins with a statement that I am a model of productivity for the whole department.

My personal experience leads me to hope that writing about sex is no longer something that anyone needs to keep hidden under a fake identity, complete with over-the-top pen name (Scarlet Veronica Filthy-Mind) and manuscripts/publications in a lockable trunk.

But I seem to be living in an oasis of exceptional acceptance. Here is the latest piece of evidence that scholarly endeavor, as practiced in universities, is still widely considered far above – or at least far separate from – sex-writing of any kind.

In March 2014, the friendly department head circulated an announcement to the rest of the English Department about a one-day conference to be held at De Montfort University in Leicester, England, on June 3. The event was titled Reforming Shakespeare: 1593 and After. Here is the description:

“This is a one-day scholarly symposium on the kinds of alteration that have occurred to Shakespeare’s writing as it has made its journey from author to readers and playgoers. ‘Reforming’ may take the sense of being given new shape as authorial or non-authorial adaptation, rewriting, borrowing or allusion and arguments about any of these processes in connection with Shakespeare fall within our purview. ‘Reforming’ can also suggest correction and improvement, including censorship, editing, and tidying up of text to make it conform to new conditions of reception, and contributions on those topics are also welcome. Send proposals for 15-minute papers to Prof X and Prof Y.”

My first reaction was: How cool is this! I noted that the conference was:

– Not being held at one of the ancient, prestigious British universities (Oxbridge)

– Apparently not dedicated to bardolatry, or reading/teaching the works of Shakespeare according to some time-honoured method, and

– All about work that could be described as Shakespeare fan-fic, innovative performances, parodies, and other spinoffs.

I wished I could find a way to get to Leicester for this event. But alas, I didn’t see how I could justify travelling all the way there from the middle of Canada while I was teaching an intense, six-week course.

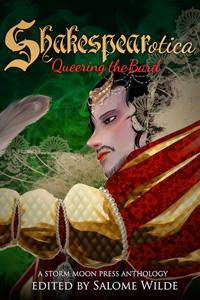

I decided to spread the word, especially to my fellow-contributors to an erotic anthology: Shakespearotica: Queering the Bard, edited by Salome Wilde (Storm Moon Press). This collection, I thought, would fit in perfectly with the theme of the one-day conference. All the stories involve “queer” (lesbian/gay/bisexual/gender-bending) characters in Shakespearean plots, and some of the stories are quite faithful to the originals. There is much same-sex emotional intensity and gender ambiguity to be found in Shakespeare’s plays, as well as much bawdiness. He wrote plays in a time when all the female parts were played by males, some of whom continued to cross-dress when they were not onstage. Whether the Bard was “queer” himself has never been decisively proven, but there are mysteries in his life that have never been completely cleared up.

I contacted Salome Wilde, U.S. editor of the anthology, and asked if she could spread the word to the rest of the contributors. I was hoping that one of them might live close enough to Leicester to make the trip worthwhile. Salome asked me for the name and contact information of one of the organizers, so I sent it to her.

A few days later, I got this email from Salome:

“Just an update to say I contacted Prof X.” This person apparently claimed there was no way to make use of the book, “as there will be no display or way to share it, and as it is in early June, I [Salome] can’t possibly attend. . . I was even thinking of giving an eBook to everyone who attended, or perhaps sending a flyer.” Apparently Prof X didn’t see how a book like Shakespearotica could possibly be included in an event named “Reforming Shakespeare.”

Sigh. I couldn’t help wondering if I (as a Canadian English instructor/erotic writer) could have bridged the cultural gap between a British Shakespeare scholar and an American erotic writer/editor, but maybe not. That gap might be unbridgeable, or I might not be the right person to bridge it. I can’t help feeling as if I threw Salome Wilde under a bus after she graciously accepted my story (loosely based on the Shakespeare comedy Twelfth Night) for the Storm Moon anthology.

Maybe I should be grateful that Prof X didn’t erupt in rage over the proposal that a discussion of Shakespeare spinoffs should be contaminated by “smut.” Even though I remind myself in these cases that things could be worse, I don’t feel grateful at all.

William Shakespeare (or whoever wrote under that name) knew in the 1590s that sex was a part of life. I wonder when the scholars who study his work will figure it out.

———-