One of the chief pleasures of writing a historical novel is discovering the details of daily life in the past so we can recreate the texture and flavor of the time. The clothing of the period is, of course, an essential focus of research to put our characters in proper attire. But because erotica writers carefully undress our characters as well, we must also learn exactly the sort of undergarments an impatient lover will encounter for full authenticity.

Most of us know about corsets, petticoats and pantalettes from historical dramas. However, mainstream movies and TV leave out one important aspect of ladies’ drawers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—they had no crotch. Indeed they were almost completely split from end to end, two free-standing leg tubes held together by little more than a waistband as you see below.

Frederick’s of Hollywood doesn’t even dare to go that far.

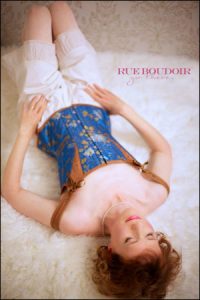

I first found out about this unspoken feature of female undergarments of the last two centuries when I was assembling a corset-friendly costume for a boudoir photo session a few years ago. I went to a local lace and antique clothing store called Lacis in the hope of finding a pair of old fashioned bloomers. To my delight, I found a pair in exactly my size for a reasonable price pictured in both photographs here. The open crotch was a surprise, but when I put the drawers on, the gap disappeared into a sort of short petticoat. Unless the wearer made an effort to spread the split seam, if you didn’t know, you’d never guess what did–or rather didn’t–lie within.

But of course, the women and men of the 1900s knew. I’ve read in several sources that working-class lovers rarely undressed fully when they had sex in Victorian times. Open-crotch drawers certainly support the logistics of that custom.

In An Intimate Affair: Women, Lingerie, and Sexuality, Jill Fields provides further illumination about the history and sexual politics of open-crotch underpants for women. Until the nineteenth century, women didn’t wear any sort of protective clothing between their legs, although surely there was some provision for menstruation. (In the time period I’m studying, women wore diaper-like pants lined with cotton wool or rags; disposable pads were just coming on the market). Little girls and boys, who were dressed alike in feminine fashion until about the age of five, wore closed pantalettes under shorter dresses. Boys then were “breeched” and wore knee-length britches, then long trousers at puberty. When girls were old enough to put up their hair and lower their skirts—more or less at puberty—they also started wearing open-crotch drawers.

Fields acknowledges that the split crotch made it easier to answer daily necessities for a woman swathed in layers of undergarments and long, heavy skirts. Some experts claimed exposing the female genitals to the air was healthy. However, Fields also emphasizes the symbolic value of the female version of drawers. Women were not supposed to wear trousers—Joan of Arc’s cross-dressing preferences were part of her heresy. If a woman wore closed-crotch garments, she would be veering too close to the appropriation of male privilege, and no real lady would dream of such transgression. Thus, the gap at the crotch symbolized an adult women’s physical difference, her availability to men, and, ironically to our modern sensibility, her feminine modesty.

Around the late 1910s, the world began to change. Skirts shortened. More women were employed outside the home in offices and factories. Women went on “dates” outside the home, danced the tango in public halls and cabarets, and rode bicycles. Modesty in public now required closed-crotch step-ins, more like our tap pants, duly decorated with lace and wider at the leg to distinguish them from men’s drawers. From the end of World War I until the present day, open-crotch panties, once the sign of submissive and respectable femininity, became associated with naughty eroticism instead.

Fields writes: “The sexual access open drawers provided could coexist with woman’s propriety only in the context of an ideology of female passionlessness and social structures of masculine domination. When women publicly asserted their own claims to sexual pleasure, political power, and economic independence, an open crotch was no longer respectable.” (p. 42)

By the 1920s, ladies were now allowed, even required, to experience sexual pleasure in marriage to keep their husbands from straying. While I view this as a positive development, Victorian prudery did allow some women the power to control the number of marital sexual encounters due to their spiritual delicacy, as well as a desire to limit families. Now a woman “owed” her husband regular sex and an enthusiastic response. For the middle-class at least, with their greater access to birth control such as the new latex condoms and diaphragms, intercourse had fewer consequences to fertility than earlier.

Fields even describes a comic novel (1926) and film (1937) called Topper by Thorne Smith where the plot revolves around a prudish wife’s conversion to the modern underpants of a “forward woman,” which improves her sex life with her husband but deprives her of her power as the moral arbiter of the family.

Nonetheless, it would be several decades more before the average woman dared to wear slacks rather than skirts over her closed-crotch undies. At a family reunion last fall, my 96-year-old aunt described the momentous day she wore pants for the first time in her life during an evening stroll with her husband through the neighborhood–with his express permission of course. In the 1950s in the summer, small-town families still gathered on their front porches after dinner to seek relief from the heat. My aunt’s heart was pounding with anxiety as she wondered how the neighbors would react to her brazen outfit. But there were no earthquakes or riots, everyone simply nodded and wished her a good evening as they had the day before.

Some revolutions are quiet, yet significant, like the closing of the crotches on ladies’ drawers.

Surprising and insightful, as usual.

How fortunate we have been to have been spared so much of this angst.

Some of these problems still linger unfortunately, but we have indeed come a long way. The clothing alone was restrictive, add in social codes and customs, and women were no doubt the “weaker sex.” I think erotica writers are doing our bit to change things, too!